Brazilian thangka artist Tiffani Rezende seems to have had much the same experience. Which may be why she titled her manuscript Life and Thangka, as it's the latter that gets most treatment in her self-published e-book. From her childhood in Brazil to traveling with her family in a caravan across Europe and Asia, Rezende presents material that would fit comfortably on a blog, personal anecdotes that only peripherally inform the brief sections on painting.

Brazilian thangka artist Tiffani Rezende seems to have had much the same experience. Which may be why she titled her manuscript Life and Thangka, as it's the latter that gets most treatment in her self-published e-book. From her childhood in Brazil to traveling with her family in a caravan across Europe and Asia, Rezende presents material that would fit comfortably on a blog, personal anecdotes that only peripherally inform the brief sections on painting.

Through charm, sincerity, and web design skills, Rezende was able to secure a spot at the painting school of the Norbulingka Institute, an organization preserving and promoting traditional Tibetan arts from the seat of the Tibetan exile government of Dharamsala, India. When I checked with them in 2007 they were not accepting applications from non-Tibetans. Rezende's experience is another fine example of how we make our own opportunities by being in the right place at the right time – and simply asking.

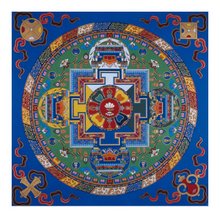

Despite Life and Thangka's paucity of thangka-related text (perhaps 10 of 81 pages; the last 20 are poetry selections), Rezende's account does provide a glimpse of Norbulingka's painting program. Students apparently spend the first few months exclusively sketching with paper and pencil. Rezende's first subject was a Buddha head, followed two months later by a complete Buddha figure and then a complete Tara. Once her sketching skills improved, she began practicing painting, starting with background items such as flowers and clouds. After four months she was painting temple walls and shortly thereafter painting small background bits of commissioned thangka.

In contrast, at Tsering (where I've been studying) students spend the mornings drawing, the afternoons painting. Drawing practice is done with a wood stylus on an oil-and-chalk covered slate board. Every student begins sketching leaves, first titled right, then tilted left, then a right and left titled pair, before moving on to lotus flowers, clouds, fire, and then ritual objects such as conch shells and dharma chakra. Perhaps after 3-4 months they begin working on a Buddha head, followed by the Buddha's unclothed body, and finally the body with the complete set of robes. This is the entirety of the first year drawing practice. Painting practice is done entirely on paper. Students first sketch leaves, lotus flowers, and ritual objects, which they then use to practice techniques of dry shading, lining, wet shading, and triple shading.

I don't see any great advantage of one school's approach over the other, except that in so far as Norbulinka students begin doing authentic work in their first year it seems they might have a bit more motivation to practice, and practice more diligently. This seemed to be the case for Rezende, who found herself energized by the opportunity to do real painting in a real temple. I felt much the same myself after doing similar work, though it came at the end of my first year and wasn't a part of the school curriculum. If all you do is practice on your slate or sketch book, you begin to loose sight of your goal, like practicing scales but never playing a song, or practicing serves without playing a set of tennis.

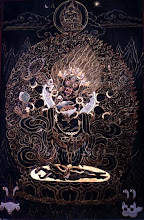

Rezende concludes her story after having finished just over a year of study at Norbulingka and her first full thangka. While this first painting would normally be filed away in the school archives, most likely to never again see the light of day, Rezende's teacher allows her to keep hers. Reflecting on why a painting that took so much effort would be hidden away, the fledgling artist comes to realize the true purpose of thangka.

It became even clearer that to paint a Thangka is not always about the painting, but also the painter, who again doesn’t mean anything, because the painter is only another instrument of the art, like the brush, the paint, canvas and light. The illustrated manifestation of a deity or a mandala becomes free of any aggregate body of someone or something mundane attached to it. This is one of the reasons why a Thangka does not usually have the painter’s signature on it - just the blessed mantra ‘om ah hum’ for pure body, speech and mind, strategically placed on the back.

Rezenda maintains a website, mostly in Portuguese (with a bit of English), featuring a blog and gallery. She returned to Brazil in 2006 and has since been painting a new Buddhist temple in city of Viamão. Photos showing the progress of the painting can be viewed here.

A Portuguese version Life and Thangka, with additional material, will be issued soon from a Brazilian publisher.

Buy the English e-book at: http://www.lulu.com/content/157908

#

0 comments:

Post a Comment