For some reason when I checked in at the Kathmandu airport the Biman agent gave me a boarding pass for only the Kathmandu-Dhaka flight. By the time I realized I didn't have a pass for the Dhaka-Bangkok flight I was already through immigration, so I let the issue go until I arrived in Bangladesh. The layover there left me plenty of time.

When I stepped up to the transit desk in Dhaka and explained my problem, the agent asked for me by name. My boarding pass was ready and had been waiting for me. I was left momentarily speechless, but when my faculties returned I expressed as sincerely as I could my thanks for the attentive service I have received both times I have flown Biman.

In Nepal or India I suppose I might have had to spend a good part of my layover sorting out this kind of problem, but now here I found myself with two hours until my boarding call. I sauntered through the Dhaka airport, which both times I have visited has seemed exceptionally quiet and uninhabited. There was one customer in the restaurant, a few watching television, and no one in the shops. The local telecom agent has provided computer stands and free internet access, but no one was using them. Except me, of course. I had thought of doing the same in the Kathmandu airport, but didn't feel like paying the $2.00 fee just to write a couple of emails.

To Biman's credit, both flights departed and arrived on schedule. The only cock-up was in not having enough vegetarian meals on the Dhaka-Bangkok leg. There was the most minimal of queuing at the Bangkok immigration counter, the bags arrived within 10 minutes of getting through immigration, and as always customs in Bangkok was a breeze – no forms to fill out, no interviews, no spot checks. Just pick up your bags and go.

As I was walking through the airport to my hotel pick-up spot, I noticed a counter selling mobile phone SIMs and stopped to inquire. Only 199bht, about US$5.00, for a SIM and 100 minutes of local calls. I took out my phone and asked the girl at the counter if the SIM would work in my phone. By the time she answered “yes” she already had the SIM card in and activated. I was again left dumbfounded. I told her that in India it had taken me half a day to do what she just did in a less than a minute. She looked like she thought I might be pulling her leg.

The guy driving the hotel shuttle van was probably not in a hurry to do anything. He just liked to drive fast and the open roads at midnight gave him the opportunity, the fastest I have traveled over land in the last six months. It is simply impossible to move at such speeds over the potted streets and dirt roads of Nepal and India.

When I got to my room, I didn't have to ask if hot water was available. I didn't have to ask for a candle or inquire about when the electricity might go out. But when I finally got down to breakfast I did have to ask someone to help me sort out my mobile phone, which was not allowing me to make any calls, even to the provider's call center. I discovered in the booklet that came with my SIM that the provider did not include a contact number that can be reached from outside its network. My most immediate need, though, wasn't the SIM itself as it was contacting my friend Krit, who was going to come by and pick me up on the way to the airport to pick up Mutsumi as she arrives from Japan. The hotel had a land line for incoming calls, but not outgoing. So to call Krit to let him know I arrived safely and was waiting for his pick-up, I had to buy a phone card for one of the public phones installed in the lobby. Except that the hotel had sold out of domestic phone cards.

Now that's more like it, I thought. This is the kind of craziness I've gotten used to. Fortunately the girl at the front desk was kind enough to let me use her mobile to call Krit and I sorted out the problem with the SIM when we went back to the airport to pick-up Mutsumi.

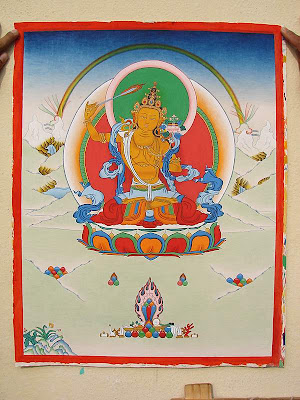

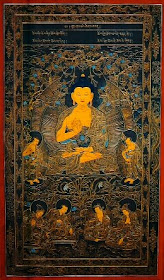

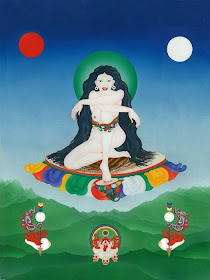

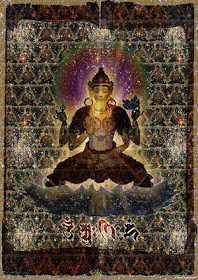

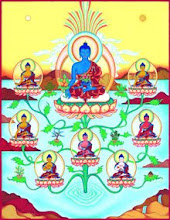

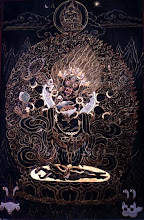

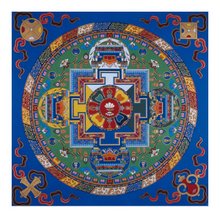

The blog post comes from a dictionary entry, the photos from Wat Lat Krabang, located just across the canal from the hotel where I spent my first night outside Nepal/India.

#