By this I don't think he meant to compliment me on the uncluttered nature of the composition or the sharpness of my lines. I think he used the word “clean” as we most commonly use it, as an antonym of “dirty.”

It might seem a strange thing to say. But I learned over the course of doing my first painting that a good painter develops and deploys in addition to fine skills of eye-hand coordination, habits of practiced carefulness and patience.

Look at the work area around a skilled painter and what you will most often see are brushes, paints and other tools thoughtfully organized. He has internalized his workspace and knows how to move around in it with little thought and little incident. Inexperienced painters tend to have more clutter. They haven't yet worked out an organizational system and tend to have more accidents, like spilling water or paint, or brushing up against their painting while reaching or reacting.

A skilled painter knows the value of properly maintaining his tools. Paint is kept in sealed jars or pots and used in amounts appropriate to the task. Palettes are washed at the end of a task or at the end of the day. Brushes are kept in such a way that there is no pressure on the hairs. A towel or tissue paper is kept nearby for wiping off brushes, palettes, or hands. Inexperienced painters tend to take their tools for granted. Not always being able to judge what might be required, they put excess paint in the palette, which is not always washed at the end of the day. This dried paint is then reused at a later date by adding water. In the interval, dust has collected on top of the dried paint and this is mixed in and added to the painting. Brushes may often be stored in such a way that the hair end becomes bent or collects dust or dirt. When they need to wipe off excess water or paint, many inexperienced painters use the cushions on which they sit. Dirt and dust are then transferred to the brush.

A skilled painter knows that the image must be allowed the time to reveal itself. There must be time to sit and watch, to see how fine lines and strokes, thin coatings of color, affect the composition. A drawing can be done in a day, but the more time there is time reflect on it, the more satisfying it can be made, just like the manuscript that benefits from not being read for several days. The finest colors and shading come not from a splash, but from the careful application of layers so thin that it may take five or ten of them to see a difference. Between those layers, one must wait; one must have the patience to let the color reveal itself. Inexperienced painters tend to be less patient; they haven't yet experienced for themselves this process of revelation and begin to believe that this time of waiting is time wasted. They are satisfied with a drawing they might otherwise like to correct if they gave their mind time to see it with fresh eyes; they add color in thick washes, looking for an immediate effect.

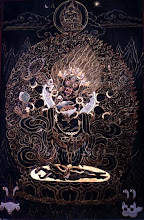

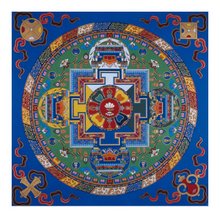

Taken together over the course of the two to three months it may take to complete a thangka, these traits and habits accumulate in the painting. The new painter tends to produce a work that is by comparison clearly dirty, marked by spots that had to be corrected because of spills, the careless pass of a brush, muddied colors, or by excess application of paint.

That my own painting was praised as “clean” is therefore something of a small accomplishment, especially as no one taught me any of this. I had to learn it as I went, by observation of those around me, and by making my own mistakes, some of which are more or less noticeable in the completed painting.

#

the discription of the prosess of care ,attention and involvment while making a thangka is so minute and meditative that it humbels the reader.thanks for this valuable sharing.

ReplyDelete